L had had trouble doing this challenge, and had made a brave effort on December 11th. He decided that for the physical thing he would go for a walk, for the emotional thing he would order a gift, and for the thinking centre he would play a chess move in a correspondence chess game, and he scheduled the times. He was going to play the chess move at 6pm, order the gift at 4pm, and go for the walk at 3pm, and he succeeded in going for the walk at 3pm. He had partially succeeded on that day, and didn't manage to keep it going through the month, in which there were a lot of things to remember and do. He had found that each centre had elements of the other two centres, but the main thing was whether one could have an intention to do something at a particular time, and then do it.

| Every day think of something to do for the moving centre, another for the feeling centre, and a third for the thinking centre. Write them down and schedule them. See if you can stick to the plan - if need be, set alarms on your phone. On each of those three occasions during the day, observe how all your centres respond, and if they all respond in the same way. |

To help her understand it a bit more, T had called the thinking centre brain work, and had planned to do the Challenge at half past three each day. She had considered it to be thinking about the Challenge and writing about the experience, and what she had done towards it or not. She had done it on the 31st December, and wrote this about the 'brain work':

The time slots pushed earlier and later like pieces of driftwood cornered by harbour walls. The time slots are not stone steps at all. When I'm at work, time slots are carved into my day by consensus planning, so that disparate humans meet, talk, reflect, plan and propose guidelines for future productive action, towards a common purpose. But the time on the holiday felt liquid and lost.

For the physical, or the body, she had planned a walk on that day.

N had not written down the things as the Challenge indicated, but he tried to do something which related to all three centres. For the emotional centre he tended to read a poem. For the physical centre he would go for a walk, or occasionally a run. For the intellectual centre he would play chess or read from a book which he knew was beyond his comprehension. He had chosen a book on the philosophy of mathematics, and tried to read a chapter a day to get into the concepts that they were talking about which he had found interesting but hard to grasp entirely. He had not been very good, he found, at the timing - he had not put it down for specific times, he would just do it at different points in the day when he remembered to do so, so he didn't order it or structure it in the way in which the exercise required.

When J had been doing physical exercise his thoughts related to either the cerebral or the romantic or heart centre, from out of what he was doing. It was the same with all of the centres. When he was doing something emotional, he did not stop thinking about it. When he was involved in the emotional side of things his consciousness was toward his head. It seemed to him that the main thrust of his feeling was around the area of the heart.

Responding to J, A said that thinking and emotion affect each other. When she thought about something, she could get emotional, even if it was just her data crunching. For her, one triggered the other one. She thought these three things were very connected, thinking, physical exercise and emotion. N noticed that when he played chess, which should be a purely intellectual process, there was a part of him that was getting emotionally involved with playing the game, and wanting to win. It was not an isolating, purely thinking, process; he was strategising. There was a part of him which was identified with the outcome of the game and part of him was hoping the person would make a mistake somewhere along the way. All the responses were not exactly purist intellectual responses. The emotional centre came in as soon as he started thinking about any process. He did not think there was a purity in each of these centres. It was very hard to separate out intellectual, emotional and physical reactions in any circumstance and even to observe them. J was surprised to hear this, because when he played chess, which was a long time ago, he did everything he could to eradicate any emotion, like I want to win, because the moment he allowed that in, he was distracted from the strategising, and the only emotion which came in, was the pleasure when someone fell into a trap that he had carefully prepared. Apart from that, anything was a distraction from the goal to get the best move, to plan as best he could, and so it was a purely intellectual exercise.

The reading then continued from Chapter 29 of Beelzebub's Tales.

Just as the duration of the movement of mechanical watches depends upon the spring they contain, so the duration of the existence of beings depends exclusively on the Bobbin-kandelnosts formed in their brains during their arising and during the process of their further formation.

Just as the spring of a watch has a winding of a definite duration, so these beings also can associate and experience only as much as the possibilities for experiencing put into them by Nature during the crystallization of those same Bobbin-kandelnosts in their brains.

They can associate and consequently exist just so much, and not a whit more nor less.

N said that, at first reading, this seemed a mechanical and unscientific way of looking at human beings and our centres and that once we went through our allocated bits in one of the centres we exhausted the system and there was no more in that area. But it seemed nevertheless to have a sort of truth in it. L said Gurdjieff was expressing, on the much larger scale of a lifetime, the earlier idea of needing balance between the three centres on the short term level of a day. Gurdjieff uses the metaphor of a watch, and what L could not make out from what he'd read so far, was whether he was suggesting that we could rewind these springs that powered the bobbin-kandelnosts, or whether that was it, that when we had used up our thinking capacity, or emotional capacity we were just left with whatever we hadn't used up.

And so, owing to all I have just said, however your favorites may exist, whatever measures they may adopt and even if, as they say, they should ‘put-themselves-in-a-glass-case,’ as soon as the contents of the Bobbin-kandelnosts crystallized in their brains are used up, one or another of their brains immediately ceases to function.

The difference between mechanical watches and your contemporary favorites is only that in mechanical watches there is one spring, while your favorites have three of these independent Bobbin-kandelnosts.

And these independent Bobbin-kandelnosts in all the three independent ‘localizations’ in three-brained beings have the following names:

- The first: the Bobbin-kandelnost of the ‘thinking-center.’

- The second: the Bobbin-kandelnost of the ‘feeling-center.’

- The third: the Bobbin-kandelnost of the ‘moving-center.’

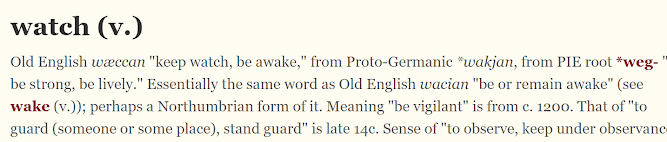

RM said that when things are crystallised, they have a limited life, but if they are not crystallised, then they are more open. When we have crystallised ideas about things, we take a position, and that is the crystallised position we have which has limited life. So we need to be watching out whether we have become crystallised in a particular view or not. If it is crystallised, the idea of the watch holds true, but if it is not crystallised, then it is much more open, free, to continue running. T was interested in the use of the word watch which has the additional connotation of observation, and wondered about the etymology. She said that winding the watch up was effort and we had to realise it was run down in order to wind it up again.

No comments:

Post a Comment